The tiny fish known as the bristlemouth is part of a detective story that bears on everything from feeding the planet and monitoring ocean health to learning how to better predict climate change.

The case centers on the ocean’s twilight zone — a dim region that extends from just below sunlit waters down to a depth of 1,000 meters, or 3,300 feet. Its darkness is broken up only by the rays that filter down on bright days. That weak light, even at its best, is insufficient to support photosynthesis and microscopic plants. So the zone cannot empower an oceanic food chain from scratch.

Given that knowledge, it was long suggested that this region — known as the mesopelagic zone, from the Greek words for “middle” and “sea” — was relatively empty. Instead, it churns with life.

Scientists have found that the creatures of the twilight zone possess an overall mass up to 10 times greater than had been estimated.

“The finding is important,” said Xabier Irigoien, a marine biologist who was part of an expedition that circumnavigated the globe to map the deep life. The enormous mass of unfamiliar creatures, he added, represent “probably 90 percent of the planet’s fish biomass,” far outnumbering tuna, cod, sharks and other better-known fishes.

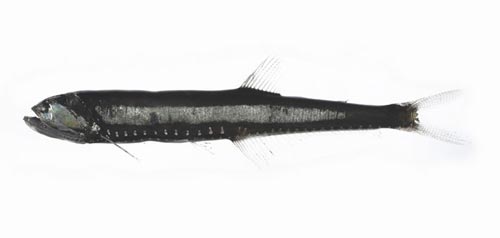

The sleuthing began in earnest when scientists first estimated the zone’s life density. Their appraisal, published in 1980 by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, became a landmark. It tallied hundreds of species like bristlemouths, lanternfish and black swallowers, which can eat creatures much larger than themselves because of their wide jaws and elastic stomachs.

The scientists totaled the catch figures from around the globe and estimated the overall mass at one billion tons. They cautioned, however, that many of the fish appeared to dart away to avoid capture, so the readings “obviously underestimate the biomass.”

In the past decade, the sleuths have sought to fill the gap, aided by better nets and sensors.

Dr. Irigoien’s expedition, which included oceanographers from Spain, Australia and Norway, sailed the globe in 2010 and 2011 and last year produced a detailed report that estimated the overall bulk of mesopelagic fishes at 10 billion tons, and perhaps even more.

That figure is not only 10 times the earlier estimate but 100 times the globe’s annual catch of seafood and 200 times the estimated biomass of the world’s 24 billion chickens, considered the most numerous vertebrate on land.

The high density of deep life, Dr. Irigoien said, raises many questions. “What do they do?” he asked. “How much do they consume? Who’s eating them? How do they influence the food chain?”

One answer teased from the twilight zone is that its inhabitants tend to swim upward to rich surface waters at night for feeding and back down to the shadows to seek protection from predators during daylight.

Commercial fishermen have made limited attempts to mine the dense swarms, but interest “is growing,” scientists in Europe and the United States reported in February. Past trawling used the deep creatures mainly for meal, oil and silage rather than human food.

The quantity of mesopelagic life is large enough to play a significant role in the cycling of global carbon, scientists say.

Seawater absorbs tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, including that produced by the burning of fossil fuels. The creatures, in turn, use carbon to build their bodies, which eventually join the rain of life detritus into the abyss. (The bodies of humans are about 18 percent carbon, and those of mesopelagic fish about 8 percent.)

This carbon uptake by mesopelagic life prompted Villy Christensen, a fish scientist at the University of British Columbia, to call the deep creatures “unrecognized allies against climate change” and to oppose their harvesting.

Peter C. Davison, a scientist at the Farallon Institute for Advanced Ecosystem Research, said climate scientists had yet to take the mass of mesopelagic life into account as a way of understanding the planet’s carbon cycle and climate change.

“It’s going to have to be dealt with,” he said, “if you want to get the models more accurate.”

—From the New York Times

Read More: An Ocean Mystery in the Trillions

Categories: Uncategorized

Overfishing Expands

Overfishing Expands  Warming Oceans Increasing Whale Entanglements

Warming Oceans Increasing Whale Entanglements  Sea Otters Work for a Comeback

Sea Otters Work for a Comeback  Plastic Waste Continues to Spread into Everything

Plastic Waste Continues to Spread into Everything

Leave a comment